We’ve been reading for years now about society’s dangerous overuse of antibiotics and the increasing number of antibiotic-resistant microbes that have resulted. While medicinal overuse of antibiotics has unsettling implications for human health, so, too does the increasing presence of antibiotics in the natural environment, which may result from the improper disposal of medicines, but also from the biotechnology field, where antibiotics are frequently used as a selection device in the lab.

“In biotech, we have for a long time relied on antibiotic and chemical selections to kill cells that we don’t want to grow,” says UC Santa Barbara chemical engineer Michelle O’Malley. “If we have a genetically engineered cell and want to get only that cell to grow among a population of cells, we give it an antibiotic resistance gene. The introduction of an antibiotic will kill all the cells that are not genetically engineered and allow only the ones we want — the genetically modified organisms [GMOs] — to survive. However, many organisms have evolved the means to get around our antibiotics, and they are a growing problem in both the biotech world and in the natural environment. The issue of antibiotic resistance is a grand challenge of our time, one that is only growing in its importance.”

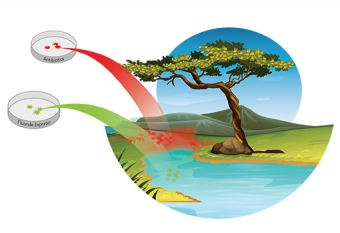

Further, GMOs come with a containment issue. “If that GMO were to get out of the lab and successfully replicate in the environment, you could not predict what traits it would introduce into the natural biological world,” O’Malley explains. “With the advent of synthetic biology, there is increasingly a risk that things we’re engineering in the lab could escape and proliferate into ecosystems where they don’t belong.”

Now, research conducted in O’Malley’s lab and published in the Oct. 29 issue of the journal Nature Communications describes a simple method to address both the overuse of antibiotics, as well as containment of GMOs. The researchers' approach, described in the paper "Engineered fluoride sensitivity enables biocontainment and selection of genetically modified yeasts," calls for replacing antibiotics in the lab with fluoride.

O’Malley describes fluoride as “a pretty-benign chemical that is abundant in the world, including in groundwater.” But, she notes, it is also toxic to microorganisms, which have evolved a gene that encodes a fluoride exporter, which protects cells by removing fluoride when it is encountered in the natural environment.

The paper describes a process developed by Justin Yoo (PhD ’19), a former graduate-student researcher in O’Malley’s lab. It involves using a common technique, called homologous recombination, to render non-functional the gene in a GMO that encodes a fluoride exporter, so that the cell can’t produce it anymore. Such a cell would still thrive in the lab, where fluoride-free distilled water is normally used, but if it escaped into the natural environment, it would die as soon as it encountered fluoride, thus preventing propagation.

Prior to this research, Yoo was collaborating with the paper’s co-author Susanna Seppala, a project scientist in O’Malley’s lab, in an effort to use yeast to characterize fluoride transport proteins that Seppala had identified in anaerobic fungi. A first step in this project was for Yoo to remove native yeast fluoride transporters.

Shortly after generating the knockout yeast strain, Yoo attended a synthetic-biology conference where he heard a talk on a novel biocontainment mechanism intended to prevent genetically modified E. coli bacteria from escaping lab environments. At that talk, he recalls, “I realized that the knockout yeast strain I had generated could potentially act as an effective biocontainment platform for yeast.”

“Essentially, what Justin did was to create a series of DNA instructions you can give to cells that will enable them to survive when fluoride is around,” O’Malley says. “Normally, if I wanted to select for a genetically engineered cell in the lab, I’d make a plasmid [a genetic structure in a cell, typically a small circular DNA strand, that can replicate independently of the chromosomes] that had an antibiotic resistance marker so that it would survive if an antibiotic was around. Justin is replacing that with the gene for these fluoride exporters.”

The method, which O’Malley says was “low-hanging fruit — Justin did all of these studies in about a month,” also addresses a simple economic limitation to antibiotic-driven cell selection in biotechnology labs. Aside from fueling the rise of resistant strains of bacteria, she says, “From a biotech standpoint, the process of creating antibiotic-resistant organisms is also pretty darn expensive. If you were going to run a ten-thousand-liter fermentation, and it may cost you thousands of dollars per fermentation to add some antibiotics, that’s a crazy amount of money.”

Notably, using fluoride at a low concentration would cost only about four cents per liter.

Clearly, says Seppala, “We’d much rather use a chemical like fluoride that’s relatively benign, abundant, and cheap, and can be used to do the same thing that is achieved using a conventional antibiotic.”

Yoo explains that the role of the fluoride transporters had only recently been elucidated, in 2013, when this project began. Emerging approaches to implementing biocontainment have focused on using biological parts that are foreign to the organism of interest, shifting focus toward what Yoo describes as “brilliant, yet complex, systems,” while perhaps diverting attention from this simpler approach.